Stop Validating & Start Co-Creating

Meet Sally and Pam. Sally is a product manager, Pam a user experience designer, and they are working on a new mobile app.

They’ve conducted customer interviews, defined their MVP, and are now working through the initial designs.

Even though their MVP will only include a fraction of their near-term vision, Pam wants two weeks to work through the design of the near-term vision, as she’s worried if they build piece by piece, they’ll end up with a Frankenstein user experience. She wants to get feedback on the near-term designs before they start building the MVP.

Sally is anxious to get the MVP out the door as soon as possible and wants Pam to focus on those designs first.

How should they proceed?

Pam is right to be worried about the overall user experience. We’ve all been frustrated by products that feel like features have been cobbled together.

Sally is also right. They should be focused on getting their MVP out the door as quickly as possible. Taking two weeks to design feels too long, especially when the majority of the work won’t impact the MVP.

The Key Assumption That We Think Saves Time But Actually Wastes It

To resolve this conflict, we need to expose a key assumption at play here.

Pam is assuming that the near-term vision is mostly right. She wants to ensure that the design of the MVP is coherent with the design of the near-term vision. She doesn’t want to design A, without knowing how A will fit with B, C, and D.

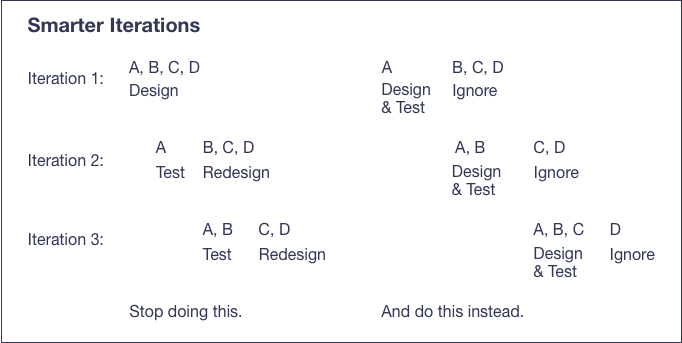

This approach would be effective if we were confident that A, B, C, and D were the exact right things to build. We don’t want to design A in isolation, without considering B, C, and D. Otherwise when we get to B, we’ll need to redesign A, and when we get to C, we’ll need to redesign A and B. This would be very inefficient.

However, if we assume that our near-term vision and our MVP are mostly wrong, then Pam’s approach doesn’t save us time. Instead, we are doing two weeks of design work that will likely be wasted.

Even though decision making research suggests that we should be prepared to be wrong, it’s actually quite hard to do this in practice. Our egos get in the way. It feels like we are right and so we proceed as if we are.

Decision-making research shows that we should be prepared to be wrong, but our egos get in the way so we proceed as if we are right. – Tweet This

But when teams instrument their products and honestly track the impact of their product changes, we see that we are wrong more often than not, even when we feel like we are right.

So if instead, we assume that we will get A wrong, or at least parts of A wrong, and that when we get to B, we’ll likely need several iterations to get B right, and so on, then taking two weeks upfront to design our near-term vision no longer makes sense.

If we assume we are likely to be wrong, Sally’s argument to get the MVP out as quickly as possible makes more sense.

The Value of Inefficient Iterations

Don’t assume your initial vision is correct. Use your iterations to build on your previous iterations.

But we also can’t ignore Pam’s concern. We do need to care about the overall user experience. This is why we iterate.

If our near-term vision includes A, B, C, and D, presumably we picked A as our MVP because it’s at the heart of the value that we intend to offer. If A doesn’t work as we expect, it puts B, C, and D at risk.

This means that we can safely ignore B, C, and D, while we work to get A right. Sally is right to focus on getting the MVP out as quickly as possible.

However, after we get A right, and we start working on B, our goal isn’t to ship B as quickly as possible. This is what leads to cobbled together designs.

At this point, our goal is to get A and B to work well together. That means we might have to change the design of A. And that’s okay.

This might feel inefficient, but it’s only inefficient when you get everything right the first time. This will rarely happen.

In the instances where we get at least some of the details wrong, this approach will be faster.

Don’t believe me? Let’s look at an example.

Suppose Pam spends two weeks designing A, B, C, and D. After launching the MVP of A, they iterate based on what they learned, and A morphs into something that no longer needs B, but instead needs E and also changes the way C needs to work.

Pam spends another two weeks cutting out the design of B, adding E, and iterating on C to reflect what they learned.

After the launch of A and E, they learn that E isn’t quite right, further impacting C. Pam spends a week iterating on A, E, and C.

You can imagine how this continues. Pam has to redesign everything each time they learn something new.

If instead Pam only designs A, she runs the risk of having to redesign A when she adds B. But here’s the key difference: While working through the options for how to make A work, she’s learned a lot about what users need from A, so she has a wealth of knowledge to draw from when modifying A to work with B.

In the previous scenario, where Pam is redesigning A, B, C, and D together, she hasn’t learned anything about A, B, C, and D yet, so her designs are guesses at best.

While Pam will still have to go through many iterations to get A, B, C, and D to work well together, each iteration is informed by the prior one. This leads to shorter cycles and faster overall design.

When each product iteration is informed by the prior one, it leads to shorter cycles and faster overall design. – Tweet This

This is counterintuitive. Let’s look at why.

Most Teams Adopt a Validation Mindset

Like Pam, we tend to use customer interactions to validate our ideas. We believe it’s our job to design the solution and the customer’s job to sign off that it works for them.

As a result, we tend to wait until we are all done with the design before we get feedback from our customers. We expect our customers to validate that we got it right.

There are several problems with this validation mindset.

First, we get feedback too late in the process. Most product teams design just ahead of their engineers’ delivery cycle. What they are validating needs to go into next week’s sprint. If it doesn’t work for the customer, the team doesn’t have time to fix it. Even if it does work, but the customer has ideas for improvement (which they always do), we rarely have time to integrate them.

When we validate our ideas, rather than co-creating with customers, we get customer feedback too late in the process to integrate it into our product. – Tweet This

Second, because of the escalation of commitment and confirmation bias, we are far less likely to act on our customer’s feedback even when we do have time.

As a refresher, the escalation of commitment is the cognitive bias where the more time and energy we invest in an idea, the more committed we become to it. If we do all of the work to design A, B, C, and D, we become committed to that design. Even those of us who have every intent to hear and integrate customer feedback will struggle with this.

And thanks to confirmation bias, the bias where we are twice as likely to hear confirming evidence than disconfirming evidence, we will miss most of the feedback from our customers that our idea isn’t working quite as we intended.

This is why we often see that even when we interview customers and usability test our ideas, we still find that our ideas didn’t have the intended impact when we release them.

This doesn’t mean that we should skip the interviews or the usability tests; it means we need to get better at both of these activities to work around our biases. (See my courses on customer interviewing and rapid prototyping.)

We need to get better at customer interviews and usability tests in order to work around our biases. – Tweet This

It also means we need to drop our validation mindset and adopt a co-creation mindset.

Why Co-Creating With Customers is the Answer

A validation mindset stems from the belief that we know best when it comes to technology. And that is true. But our customers know best when it comes to their own needs.

We know best when it comes to technology expertise, but our customers know best when it comes to their own needs. – Tweet This

Now some of you might be thinking of Steve Jobs who argued that customers don’t know what they want or that no one would have known to ask for the first iPhone. So let’s be clear on this distinction.

Customers don’t know what technology can do. They would have never asked for the iPhone because they didn’t know the iPhone was possible. However, they did know that they hated checking their voice mail, that texting using numbers was incredibly painful, and that small screens made it hard to find the contact you wanted to call.

Apple applied their technology expertise to solve these problems and many more with the first iPhone. There’s no way they could have done that without learning that these were important problems in the first place.

Successful products are the result of technology expertise applied to real customer needs. Co-creating with customers allows you to ensure that you are building something that your customers want or need.

Successful products are the result of technology expertise applied to real customer needs. – Tweet This

So what does co-creating look like?

Unlock the Power of Co-Creating Solutions

We make product decisions every week, therefore we need to engage with our customers every week. Many teams struggle with this. They argue that they they can’t turn around designs fast enough to engage with customers every week. But this is a validation mindset creeping back in.

We can’t finish production ready designs every week, but we can and should be iterating on last week’s work. If we drop our validation mindset and adopt a co-creation mindset, we can get feedback from our customers while we are still in the messy middle of iterating on our design.

Instead of asking our customers, “Does this design work?” when we get to a final design that we are happy with, we can show our customers three or four design ideas that we are playing with. We can ask them, “What do you think of these options?”

This subtle shift addresses both of the problems we identified above and has two added benefits.

First, we are getting feedback from our customers much earlier in the design process. It’s much easier to iterate on sketches and wireframes than to iterate on production-ready designs. So when our customers give us feedback, we are much more likely to integrate it.

Second, we are less prone to escalation of commitment and confirmation bias, because we have invested less time into each idea. We are also exploring a compare and contrast decision rather than a whether or not decision, which is going to help guard against confirmation bias.

In addition to solving our two problems, we also get two added benefits.

The first added benefit is that when we share less-polished designs, and especially when we share multiple options, our customers are much more likely to give us honest feedback. It’s clear to them that we are still designing and they will be less concerned with hurting our feelings.

And the second benefit is that they will be more likely to jump in and share new options that we didn’t consider. Now some designers might fear that this will lead to “design by committee.” You don’t have to use your customers’ options. But you will learn a lot about their needs from the options that they suggest—and that is priceless.

How can you shift your mindset from validation to co-creation? If you are interested in practicing your co-creation skills, check out my Rapid Prototyping course.

from : https://www.producttalk.org

Leave a commment, please!

ReplyDelete